In virtue of Singapore's education system

Written by Sami

Rehearse: (verb)3

- practise (a play, piece of music, or other work) for later public performance

- State (a list of points, especially those that have been made many times before); enumerate.

“To rehearse”, Celia thought, “meant to repeat a series of actions in the ways we were taught – or conditioned – to do”. With a finger in Hook and Eye4, she recalled Jeremy’s “Sophia’s Party”, having found its evaluation of a typical national day reunion intriguing. How often do we trade the comfort of old tales for new ones? And should we be asking more about the narratives and practices of our everyday?

Such things were fitting preoccupations for days like this. On it’s last birthday, Singapore had taken this as an opportunity to showcase both “the old and the new” and its position as a multicultural hotpot.5 Schools did not shy away from this either, with its students and staff donned in red and white for this memorable occasion.6

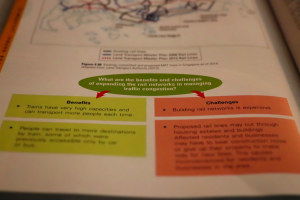

Yet, Celia could not shake the feeling that something lay beneath this glamour. And she was not wrong, her exposure to works like Finnbar’s “Subterranean Singapore 2065”7 has made her realise that privileges and luxuries came at another’s misery and oppression. Finnbar’s references to man’s overextraction from nature and the exploitation of labour had made her shudder many a times, as she remembered projects like the Cross-Island Line8 or the ongoing migrant worker crisis.

She rested her chin on the arm of a sofa, stretching her hand forward before inspecting it. Are stories of national solidarity not themselves a hindrance to true community and inclusivity? Surely, that had to be the case, if in the name of some national celebration, valid environmental concerns were reduced simply to the “agenda” of “any interest group”.10 Or, Celia humored, if restoration of this supposed religious harmony came at the sacrifice of the very minority voices it was meant to support.11

She had plunged into a deep hole with that one. The walls piping hot, erupted into a volatile mess of memory. State elections were the fumes that wrapped around her, and she could only dare imagine how tight they must have been for those12 13 they were after. To pursue a Singapore that is stronger together should not involve discrediting the experiences that are “foreign” or “do not belong”14, but instead evaluating and more importantly, creating the space and vocabulary for open discussion15.

Still, placing her book nicely back on the table, she found herself perplexed. While individually, we do ‘rehearse’ these old narratives, it is clearly the institutions and systems that induce and perpetuate them in the first place. The education system (that Celia has known to shun) holds great power in this regard, given that it reinforces the values and stories of the generations to come (what Bourdieu posits about education’s complicity in social reproduction16 bears resemblance here). Even in her readings, she had chanced upon this exact line, of which she had studiously underlined:

….reviewing educational policies and changes that are aimed to…

Strengthen national identity, values, and social cohesion, and, in the process, sustain Singapore’s society regardless of race, language, or religion.

- Goh Chor Boon & S. Gopinathan, The Development of Education in Singapore since 196517

Celia bit her lip but was unable to stifle her laughter – to think those above would still use the same excuse that Singaporeans were not ready!18 They never will be, if trained not to be! Perhaps that is what a ‘rehearsal’ meant…

What history meant to Celia was always a blur. Not the kind where she was unable to see anything entirely; but like an unfocused camera lens, her understanding of it was fluid, brushing past without her knowing all the details.

It was only after the revival of a black lives movement19 that she grew interested in the idea of colonisation. Colonisation. Oh, which of its legacies persevered on? She would wonder. She always would.

For it was upon moving away from it that Singapore had known it had to expand its education programme promptly.20 The reason? Survival as a newly independent state. And to that end, it developed an “expert-oriented industrialisation strategy”, hinging on a literate and trained workforce.21

As noble as this cause was, Celia hazards that it’s consequences still reign till today, pointing to the ‘Kiasuism’ and the overemphasis on certification and STEM jobs that remain as hallmarks of this little nation. She remembered too, that in a fit to combat fears of ‘Westernisation’, the incumbent had placed emphasis on ’Asianisation’, which saw the introduction of the Special Assistance Plan (SAP), channeling funds disproportionately towards the Chinese.22 Recently, Celia had also stumbled upon the term “CMIO Multiculturalism”, which was used to describe the brand of multiculturalism that Singapore had embraced in its ‘post-colonial’ days.23 It relied mostly on generalised racial categories and peoples’ blind faith in the state to maintain inter-ethic peace and harmony. The move harkens back to when the Jackson plan of 1822 was enacted, which witnessed the (geographical and institutionalised) segregation of races and consequent creation of both a language and racial hierarchy (typically favouring Europeans and the Chinese)24.

As much as our history textbooks would like us to forget, accounts of colonial Singapore continue to verbalise the reliance on indentured labour at homes, on plantations, in construction, and public projects.25 This sounds slightly familiar, does it not? Eerie was perhaps not the right word to describe Celia’s emotions, but suffice to say she was gravely distressed. How easy it has been, to erase the oppressed from history, honor them selectively (as it were with the portrayal of Samsui women in 2015’s NDP26) , and proclaim religious harmony. Joanne’s comparison of Singapore to Westworld and the image of the city being stripped bare – multiculturalism, contemporary excellence and all -, injustice unveiled, was especially stark now:

“At first lauded for its gold-standard pandemic control—the sleek city-state, as the one in Westworld where all seems modern, precise, and carefully curated—the island finally succumbed to its open secret: the immense underclass of foreign workers, the enforced poverty and apartheid-like living conditions that sustain the unsustainable.”

- Joanne Leow, “This is Singapore”On Watching Westworld in the Diaspora27

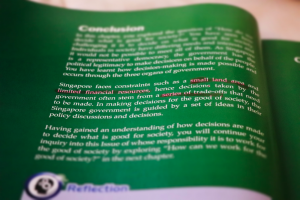

Yet the nation-state had insisted on its strive towards a multicultural identity, and emerging from it was Racial Harmony Day, launched in 199728 (Celia cocked her head to the side when she found out that this was 34 years after the race riots! 34! And it was used to justify the ISA prior to that29…). and done as part of Singapore’s National Education (NE) programme. How such a programme came to be was apparently from then Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong, upon realisation that there was a “serious gap in knowledge” among the youth on post-war history30 (- using the very applicable life skills taught in school, she could not help but compare and contrast this to what he said some time ago31). NE has, since then, been “infused” into every aspect of school life.32

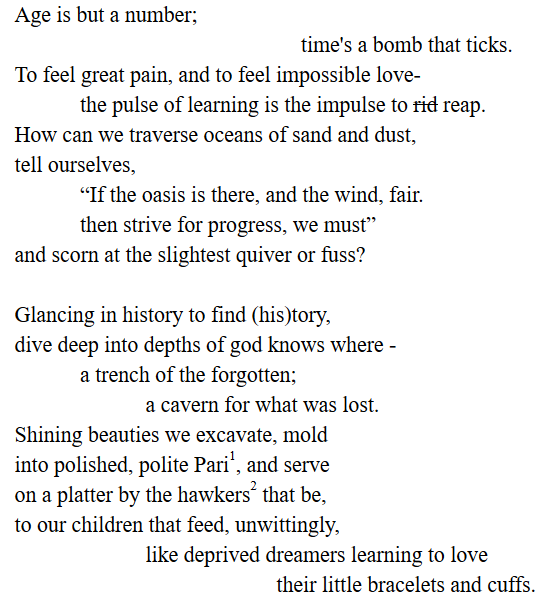

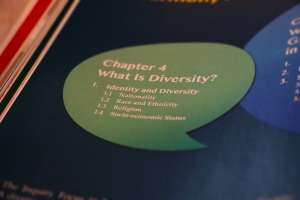

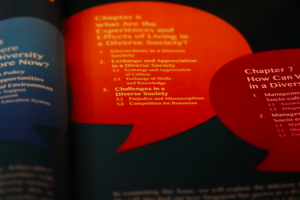

Once, Celia had taken a deep dive into her old textbooks and diaries – whether for nostalgia or frustration, she would not know. Pictures of National Day and Total defence day were part of that pile; And she viewed them with new awareness. Simply put, in championing the cause of diversity and racial harmony, these official narratives of “rituals” and “riots” were a means of “disciplining difference”33. Calling out the irony in how days like Racial Harmony Day are still “an occasion to dress up” and “sidestep difficult questions”34, she indulges in the possibility of ‘celebrating’ Check Your Privilege Day35 instead. Diversity as a concept was covered in social studies, but it’s narrow scope, combined with the depiction of challenges as solely interpersonal, disconnected it from wider systems and dynamics. Like a TV on replay, she would say.

Indeed, as much as this Island-city has ‘progressed’, it never seemed to have recovered from past trauma. It’s success story is always “despite” or “in spite of” its size and lack of resources, not “because of” as writers like Sudhir Vadaketh have suggested36. Celia agreed that Singapore’s vulnerability may very well be a “social construct created by those in power”. How else would society accept the trade-offs made?

As a person who strongly believed that win-wins were also possible, having to revisit such inherently zero-sum narratives did not sit well with Celia. Unnerving as it was, she had to flip through pages and pages that showed the government making “trade-offs” with people’s best interest in mind, often skimming over the real human and socio-cultural cost of their ‘developments’. They also rarely paid heed to the alternative voices that had as much of an equal role in the shaping of our nationhood37.

Noticeably, the problem lies not only in what was portrayed, but what has fallen through the gaps. Celia has always been wary of the tension belying what she learnt in school, and the world around her. An image of a placard from last year’s climate rally38, saying “O Lvls soon but so is irreversible climate crisis“ was something that left an imprint in her mind. Hearing the crowd chant “What do we want? Climate Action!!” really made her feel as though all the case studies and solutions could never amount to the passion and sensitivity culminating in that moment, and it was madness. Madness in the sense that what prepared her for the intricacies of the world was going out into it herself. It was not school, not some 21st century competencies39, and probably not a “refreshed curriculum”.40

So often has the education system conditioned us to tend towards objectivity and categorisation in the face of complexity, and pursue sheer productivity in lieu of redundancy and creativity.41 She notices this from the way we divide into Science and Art streams42, have enrichments like the Humanities programme43 and Creative Arts programme44 reserved for ‘the talented’, to the so-called “paradox of meritocracy”.45

Where this positions Celia is rather precarious. On one hand, she is haunted by the knowledge that her education (and that of the future) remains disharmonised with the many actors, structures and crises that are ultimately intersectional and in urgent need for action. And the system continues to disaffirm LGBTQ+ students46, facilitate racial discrimination47 and widen inequality (she points to Dr Teo Yeo Yenn and her comments on “hierarchy” and what the system “rewards” and “punishes”)48. Yet, on the other, she is helplessly disempowered, unable to effect change.

She thus questions what this means for a student’s political literacy and civic participation. Should they not have the ability and agency to stand with the causes that they hold dearly? To question the narratives and practices as she is now? Even recently, a school cautions against political discourse49 when there has long been calls for greater strides made in this regard (See this CNA Talking Point in 201450, PSP’s launch conference51, or some party manifestos52 53 ). We need more youth like Raeesah54, Celia thinks, who will call out what is truly wrong with our ways of perceiving and doing, and then work towards changing that.

In virtue of Singapore’s education system, Celia is hopeful that things can shift for the better. Success in such a system meant embracing “culturally dominant virtues” of Abundance, Control, Conviction, Competition, and Individualism, as William Throop has so gracefully put into words.55 Now, it is with this, that we can know “what” to move away from, asking “why” and then “how” as we chart a path towards a truly holistic and value-based education for the future. Throop calls this “transition virtues” of Frugality, Adaptation, Humility, Collaboration, and Systems-thinking, to which Celia fervently nods.

As Nominated Member of Parliament Kuik Shiao-Yin argued before during the 2016 Budget Debates56, policy changes without the aligned cultural interventions will be limited at best. Simply refreshing or introducing a syllabus into the curriculum is not the same as having reforms that tackle root causes – like the one suggested for sexual education57 – or dismantling the system entirely.

Uprooting fundamental concerns would require the challenging and countering of narratives, long-held. It requires the relooking of principles like our shared confucian values58 with questions to be asked: “What should we hold onto? What should we keep?” Only then can Celia aspire for the day where autonomous moral reasoning and serious self-reflection will be appreciated. Democratic rights are something we all have. So empowered we must be; to conquer the trade-offs, we resist.

“2020 was the closest that we have come to a viable opposition presence”, Carissa Cheow says, while reiterating that there is still an arduous road ahead.59 Celia feels a similar stir every time she squeals with glee when reading articles like Kokila’s “Being Mao Mao”60, which fill her with this undying resolve to upheave oceans, however deep the Mariana Trench may be. It is with this same sensibility that she regards festivals like Activism in Crisis61, not as epitomes (she feels they are), but as tasters of more to come.62

This national day, Celia wishes for more dialogues around justice and moral leadership; more spaces for difficult conversations to be had and acted upon; more interdisciplinary, intergenerational and cross-cultural engagements that involve the whole of society. And that requires everyone to humble themselves and embrace the prospect of uncertainty, inclusivity and bountiful imagination for all.

With that, Celia leaves you with this:

“Understandably, educational systems, especially those that have existed for many decades in developing countries, are inherently conservative institutions, and change is often resisted. But globalisation will create inevitable changes. For teacher education and training in Singapore, remaining unchanged will lead to degeneration.”

- Goh Chor Boon & Lee Sing kong,Making Teacher Education Response and Relevant

Footnotes

- Pari is Stingray in Indonesian (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ikan_bakar). They are a delicacy in Singapore (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sambal_stingray)

- Hawker centres are food courts in Singapore (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hawker_centre

About the Author:

What does it mean to dream? For someone like Sami, that was all she knew. Imagination was her lifeblood and stories were the source, taking her to places beyond. As words became sentences, and sentences became expository, those four lines on the walls of possibilities – she knew so perfectly -, suddenly, vanished. It was as though the shabby foundations beneath her had sunken into the floor of this exasperating, lovable city, along with all the makeshift constructions which, allegedly, compartmentalized and effectively utilized, space. And to think she would ever stop dreaming.

1 Comment

Qiao Tong · July 29, 2020 at 2:04 pm

Hello, Qiao Tong here, thought it will be nice to leave you a message here in case you come across it. I wanted to say thank you for your message.

I like the way you did up your presentation and your writing too 🙂 It was very informative and clear!