The Faded History of our Island Nation, and the Rise of the Garden City

Written by Rukhsar

What do you think of when someone says to you “Singapore”? Many Singaporeans would often reply that Singapore is a Garden City. Yet, this is a narrative and image built and pushed by the Singaporean government to portray our country as a unique one with a special identity that sets us apart from other nations. However, I want you, as the reader, to reflect on this narrative a little bit more. What exactly is a Garden City and what is the criteria to truly be one? If you peel back the layers of what it truly means to be a Garden City, does Singapore actually check all the boxes? These are the questions you and I are going to attempt to find the answers to in this article.

First, let us find out how Singapore got this name i.e the Garden City. On the 11th of May 1967, our late Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew introduced the “Garden City” vision in order to “transform Singapore into a city with abundant lush greenery and a clean environment in order to make life more pleasant for the people.” 1. Upon the introduction of his vision, tree-planting initiatives started to rise in number. By June 2014, 1.4 million trees were newly planted. Impressive, right? For us locals, one of the most prominent and distinctive lived experiences of Singapore would be the countless trees and grass patches lining the pathways and roads almost everywhere in our neighbourhood. This is what we are familiar with, what we consider our home and what we associate with the term “Garden City”. A Singapore without trees everywhere would be a peculiar sight to behold.

The late PM Lee Kuan Yew seemed to understand and recognise the value of nature in helping relieve people’s state of minds from the immense stress as a result of the fast-paced and demanding society that we live in. PM Lee’s vision kick-started Singapore’s long and continuing journey of pursuing green urbanism, which is the practice of creating communities beneficial to humans and the environment. Green urbanism is thought to play a significant part in making a city liveable. Besides reducing the large amounts of carbon emissions our tiny city is guilty of producing and lowering the high temperatures our tropical island city is notorious for, it has very significant benefits to our mental health, as previously mentioned. This shows that nature plays a vital role in ensuring the well-being of city dwellers like us and the focus of green urbanism in our city’s urban development.

Besides the trees and grass patches lining our pathways and roads, Singapore also makes an effort to build and integrate many parks and green spaces throughout the island, which again lays testament to our authorities’ adoption of green urbanism. The parks and nature reserves conserved by the authorities help Singaporeans escape from their busy schedules and provide temporary relief from stress. It also helps people maintain a healthy lifestyle as parks are multi-purpose and are utilised for exercise. It has been suggested that connecting with nature benefits one’s mental and psychological health. Psychologist S. Kaplan suggests that nature has specific restorative effects on the brain’s executive attention system 2 which refers to an individual’s capacity to choose what they pay attention to and what they ignore.[1] At work, most of us are glued to the computer screens for hours on end. This takes up quite a bit of our executive attention and thus our brain’s energy. Interacting with nature counteracts that, as doing so helps the brain to replenish its depleted energy. For city dwellers like us, this is very beneficial and can even be argued to be necessary, in order to ensure that our mental health is in tip-top shape in a society where everything moves at a face pace. Thus, this further enforces the relationship existing between Singaporeans and nature and shows just how much we rely on nature to relieve our stress.

Now, when we think of the term “Garden City”, we would most likely associate it with things like a city being one with nature, where both natural and man-made environments coexist harmoniously. This would thus extend to connotations of Singapore being an environmentally conscious society and that eco-friendliness and green measures are a norm. This means going beyond just building parks for relaxation and exercise and to actively integrate green policies at the institutional level so as to create a nation that can truly identify with our country being crowned a Garden City.

Alternatively, the narrative and image behind the “Garden City” can also be associated with aesthetic purposes, simply crafted to form a unique identity of our country that can be capitalised for tourism and made attractive to other countries. The benefits that tourism has brought to Singapore is sizable. It has helped bring in large amounts of foreign direct investment, increased employment rates and helped with our economic growth. It does make sense for a small island country like Singapore with little to no natural resources, to use tourism as an important driving force of economic development. Once again, we can see that the narrative and identity created behind “Garden City” is pushed for socio-economic development, even if it appears to do good for the environment, and arguably so as space is set aside for flora and fauna. It highlights the narrative of “Garden City” being sold to the international community as a tourist hotspot and hub, a place worthy of being visited and marvelled at. It also reflects the priorities of the government. Not many countries have such a unique identity of being a city in a garden after all.

However, the reality is that Singapore continues to fall short at being environmentally sustainable in more ways than one. This is the case even now, where environmental consciousness and awareness have been spreading like wildfire among the younger generation, who are better informed on the issue. Did you know that Singapore is ranked 27th out of 142 countries in terms of carbon emissions per capita3 and that we generated 7.7 million tonnes of waste last year, equivalent to the weight of 530,000 double-decker buses?4 With these statistics in mind, simply planting trees at the side of the road and preaching that our nation is a Garden City is not going to cut it unless we ensure that issues like our carbon footprint and solid waste generation, are addressed so as to achieve sustainability at all levels.

If we trace back Singapore’s development, we can see that our “Garden City” is built on practices not actually beneficial to the environment. The city-state has increasingly shown that it will continue making plans for socio-economic development at the expense of the environment and affect marginalised groups.

Let us take a look at the very early stages of Singapore’s urban development in the 1970s-80s. Singapore is made up of 64 islands, including the mainland where the city is centered on. One of the islands, Pulau Seking, is an island off Singapore’s south coast and is known to be the “Last Kampung Island”, home to the last indigenous Malay community in Singapore. The island was believed to have roots dating back beyond 1819 with cultural anthropologists saying its villagers were the descendants of the original Orang Selat, also known as Orang Laut, who knew Sir Stamford Raffles. This means that Pulau Seking had a strong possibility of cultural and historical significance. Due to plans to convert Pulau Seking into a landfill, the last few inhabitants of Pulau Seking were forced to leave their island lives and relocate to the mainland in 1994.

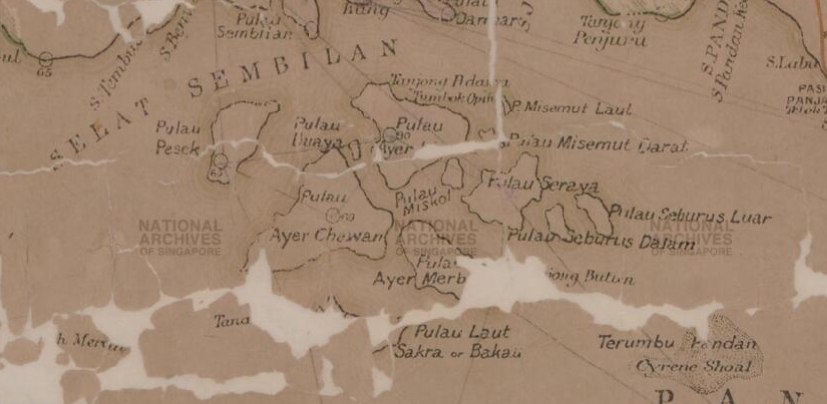

As time passed by, the inhabitants of other islands were evicted as Singapore’s urban development kicked into full gear. Today, Singapore’s Southwest islands are the sites of petrochemical industries. In the 1990s, the Southwest islands were reclaimed to form one main island called Jurong island. However, they were previously home to kampungs such as Ayer Chawan and Ayer Merbau, which once had their own cemeteries. While few traces of history remain about the Southwest Islands, there are some sources that suggest that the islands once had a maze of hideouts for pirates to use when escaping after their sea raids on passing vessels.5 Just like Pulau Seking, the Southwest islands were home to Malay indigenous islanders in the past. It is to be noted that the islanders were evicted and the islands redeveloped for economic gains as the government recognised the economic value of developing petrochemical industries on the islands so as to drive economic growth. This once again reflects on the priorities of the government and that they value economic development over the preservation of the culture and history of the islands that were once home to many of Singapore’s indigenous Malay people.

This, and the eviction of the inhabitants of Pulau Seking for it to be converted to a landfill shows that the Singaporean government has neglected to consider the loss of important heritage and history in the pursuit of modern development. For the sake of socio-economic development for those living on the mainland, the other islands and their rich environmental history were sacrificed, and their people losing their identity and culture as well as their heritage.

It may then be argued that there is no environmental justice, which according to the The United States Environmental Protection Agency means the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies6, being served for these evicted indigenous communities. They not only feel like foreigners but are forced to integrate into a new environment and society which they are not used to. The Singaporean government has also left this part of history out of the education system, as I for one, have not heard of such indigenous communities

In an interview posted to Youtube, Saniah Binte Ali, the wife of the late and last penghulu of Pulau Seking, Mohamed Yatim Bin Akib, recounts her life on Pulau Seking; “Nenek bebas. Boleh jalan sana jalan sini. Kat sini, macam terkurung. Nenek tak selesa duduk sini, tinggal lagi terpaksa. Bila Nenek ingat pulau, Nenek tambah sengsara” (Island Nation)

Not only that, despite the efforts the Singaporean government has put in for participatory planning which refers to urban planning involving the public, they often fail to meaningfully engage with the different communities and stakeholders involved regarding various issues. One recent example is the construction of the Cross Island Line. It was planned to be one of the new MRT train tracks that the government aimed to build in the next few years in order to improve connectivity, reduce the travelling time and to make the lives of commuters more convenient and efficient. The Land Transport Authority had planned out two possible routes, one being the direct route of running underneath the Central Catchment Reserve (CCNR) and the alternative route of skirting around the CCNR. Of course, building the train track has its economic benefits, such as reducing the time spent travelling to work, increasing labour productivity and thus contributing to economic growth.

When the plans were revealed and the two possible routes scrutinised by the public, the government faced strong public backlash. There was pressure, particularly from environmentalists and experts in the field of environmental conservation, on the authorities to reconsider their plans. There was some contention between the authorities and the environmental groups concerning the implications the construction of the train track would have on the biodiversity of the reserve. Hence, the Land Transport Authority (LTA) hired a global environmental consultancy to assess the impacts of building the train line running underneath the CCNR. The study found that some of the negative impacts of constructing the train track following the direct route include; deforestation of forests affecting the habitats of the plants and animals, sedimentation of streams within Windsor Nature Park. This is only some of the many implications constructing the train track underneath the CCNR would have on the natural environment.

Despite years of back and forth between the government and other relevant stakeholders in considering the perspectives and feedback from environmental groups, it was announced in January 2019 by Transport Minister Khaw Boon Wan that the Cross Island Line would be built along the direct route i.e it would run underneath and cut through the CCNR. The news, of course, came as a big shock to the environmental groups and people that had been contesting the direct route. However, it did not come as a surprise that the authorities would ultimately pick the more economically feasible alternative route of skirting around the CCNR since it would mean that there will be no additional cost of SG$2 billion incurred and that the travelling time would not be increased by four minutes, which as previously explained, would have meant a dampening of our economic growth due to decreased labour productivity.

Here, we start to wonder whether the government’s engagement in participatory planning actually means that they thoroughly consider the people’s perspectives and feedback. As seen from the Pulau Seking case, we see that the government constantly makes trade-offs that are in favour of socio-economic development for the people in the city and do not really take into account the loss of environmental heritage. The Cross-Island Line was planned to achieve exactly that, even if it meant that the little but extremely precious biodiversity we have concentrated in the CCNR, which is the largest nature reserve on our island, would be jeopardised.

The government’s pursuit of a Garden City is one that disregards our rich history as a tropical island nation and instead focuses on crafting the perfect image and built environment of a “Garden City” for Singapore. This has caused Singapore to lose its sight on actually achieving sustainability across all levels. From the way the ground up civic-action are often unable to influence the government’s economic plans, to the lack of consideration and sensitivity in ripping away indigenous Malay communities from their beloved island homes to build a landfill. The prioritisation of socio-economic development at the expense of the environment has led to the rise of the Garden City, a carefully curated and shallow narrative of Singapore to be sold to tourists.

If Singapore truly wants to go deeper beyond simply planting trees at the sides of the roads and calling it a day, both the government and the people have to be actively creating and enforcing policies and practices that help the environment and can achieve sustainability at the institutional level. The Covid-19 pandemic has shown just how much nature can thrive in the reduction of human factors. Climate change is also a reminder that we need to diversify our economy and invest in sustainable energy sources. Singapore is a low-lying island. This means that we are at risk of sinking in the wake of rising sea levels and flooding because of intense heavy rainfall as a result of global warming. We cannot deny that Singapore has done a commendable job and put in large amounts of efforts to adapt to the effects of such events. Recently, the government announced a new coastal and flood protection fund, with an initial injection of $5 billion and a subsequent $100 billion over the next 100 years, will be set up to help protect Singapore against rising sea levels. 7

Yet, we, as a nation, have to recognise the root causes of such events; global warming. Global warming’s main contributor is the persistent increases in carbon emissions globally. Singapore, despite being small, is guilty of producing large amounts of carbon emissions annually. Singapore generated 52.5 million tonnes of greenhouse gases in 2017, said Dr Koh Poh Koon, Senior Minister of State for Trade and Industry. 8 This is estimated to be 0.11 percent of global emissions 9 . In terms of carbon emissions per capita, Singapore ranks 27th out of 142 countries based on the latest International Energy Agency (IEA) data. 10 This is extremely worrying. A country as small as Singapore should not be producing this much carbon emissions per capita. It simply does not add up.

This is why it is vital for the Singaporean government and Singaporeans alike to change our mindsets on the environment and also to start implementing green policies and measures that will not only help change our mindsets but also to ensure environmental sustainability. In order to do that, there are a number of ways to make sure both the government and the people understand and recognise the importance of the environment. We need to cultivate care and concern at the individual level but also at the societal level.

We can start making changes in the education system. We should teach students about the environment and how vital it is to human survival, not only at its basic function of providing us with oxygen to breathe, but all the way to its role in mitigating climate change. It would do good to teach them such information since young as climate change concerns the younger generation the most since issues of intergenerational equity is also another matter. We need to ensure that all students know of these things across all levels, even for students who do not take up subjects that already have this information in their syllabus, like Biology and Geography.

Besides teaching, there are other ways to cultivate love and concern for the natural environment in people. For example, we can make sure that every student has an opportunity to experience gardening, whether by making it a compulsory module or simply encouraging them to try it out. Of course, there have been some efforts in producing an environmentally conscious generation. The government has tried their best to instill habits of recycling, switching off lights and turning off the water taps when not in use. By encouraging and cultivating these habits in people since young, they are made more aware of just how valuable their individual actions have positive impacts on the environment.

However, the problem with only enacting green habits and measures at the individual level is that it transfers most of the responsibility of caring for the environment to the individual only. This is not going to help in the grand scheme of things as most of the carbon emissions released from Singapore is by the industries here; approximately 60% of the 0.11% carbon emissions Singapore releases. Three quarters out of the 60% is by the petrochemical and refining industries 11. This means that the Singaporean government has to step up in enforcing policies and quotas on the industries in our nation so as to significantly reduce carbon emissions released by our country as a whole. This is where sustainability at the institutional level is important and a matter of policy.

It is not to be said that individual actions do not matter and that individuals should not bear some degree responsibility in caring for the environment. People do have a hand in contributing to carbon emissions; consumerism culture, increasing demand for beef, unsustainable fast fashion and so on. However, when people feel that in order to save the world they have to carry out actions like using metal or bamboo straws instead of plastic or to start bringing their own bags to the supermarket, it actually paralyses change. Global challenges must be tackled by institutions. Personal sacrifices alone cannot be the only way to tackle climate change. 12 Needless to say, there has been an increasing amount of pressure against the government by the people to enact change at the institutional level.

However, the pressure on the government by the people can only be felt depending on a mindset change at the institutional level, which is crucial. By having a mindset that focuses on and understands the significance of being environmentally sustainable, the policies and measures that are created will reflect said mindset and have a positive impact on the environment in Singapore, allowing us to truly be able to call ourselves a Garden City.

Firstly, the government has to stop prioritising only socio-economic development at the expense of the environment. As seen from the examples explained earlier, there are many times where the government has failed to fully take into consideration the impact their economic plans have on the wider natural environment. If we want to ensure that the small reserves of the natural environment are conserved on our islands, there has to be more attention and effort given in the initiatives or measures that aim to do just that. This means that there has to be a high level of political commitment in helping the environment. This entails more attention being given to the people on the ground who are fighting for the protection of nature in Singapore, such as environmental groups and experts. From there, more action can be taken in ensuring that environmental sustainability can be achieved.

Secondly, the authorities can do more to create and enforce environmental policies on the industries here, especially in the petrochemical industry as they are responsible for a substantial amount of our nation’s carbon emissions. Currently, Singapore has been doing its part in reducing greenhouse gas emissions by introducing new initiatives. This includes the Commercial Vehicle Emissions Scheme for new light goods vehicles, which make up the largest proportion of commercial vehicles, and a $24.8 million Climate-Friendly Household Package. Households in one-to three-room Housing Board flats will receive a one-off $150 voucher to purchase more energy-efficient refrigerator models.13 Yet, most of them focus on what households can do to reduce their carbon footprint. This once again highlights the transference of responsibility in helping the environment to the individuals. This thus means there is an urgent need for the government to create policies targeting large industries that are also, if not more responsible for most of Singapore’s carbon emissions.

Thirdly, the government has to loosen the restrictions placed on freedom of assembly when it comes to protesting for more action against climate change. Recently, two teenagers aged 18 and 20 were investigated for protesting climate action signs without permits14. While there is no denying that participating in a public assembly without a police permit in Singapore is illegal, the authorities could possibly have thought more about why more youths are stepping up to push for more action in reaching zero net emissions such as the two teens. Through analysing such events, it is possible for them to thus recognise and understand why environmental issues are so important for our generation. From there, the authorities can start working on creating a future that is environmentally secure for the new generations.

There are many ways in which the relevant authorities can pull their weight in ensuring that a more environmentally sustainable future is achieved. The methods listed above are only the tip of the iceberg in the many different actions that can be taken by relevant stakeholders. The problem is not coming up with solutions for problems pertaining to the environment and sustainability, but rather the enforcement of such solutions. It cannot be denied that throughout the journey in reaching sustainability at the institutional level, the government, other relevant stakeholders and the people will face many challenges. It is, after all, difficult in enacting systemic change. Hence, the whole nation has a lot more to do in helping the environment and to ensure that sustainability is pursued at all levels and at the national scale. Once we have achieved a sustainable future, or at least one that is close to it, we can then proudly call ourselves a Garden City.

About the Author:

Hello there! I’m passionate about a wide range of topics ranging from geography to politics to making sticker packs for my friends ;D!! Ultimately, I’m just trying my best to make this world a less ignorant place <3

0 Comments